There are nearly three dozen rockfish species in Alaska, but only about 1/3 of those are commonly pursued by anglers. Of these, the most common by far are black rockfish (sebastes melanops). Another popular species, the yelloweye (sebastes ruberrimus), is very susceptible to overfishing, and in recent years has seen protective measures installed in order to ensure the health of the species. Interestingly, both fish have been misnamed by anglers. Black rockfish are often mistakenly referred to as "black bass" (there are no seabass in Alaska) and yelloweye are commonly called "red snapper" (there are no red snapper in Alaska). If you're new to rockfishing, using the proper terminology on the charter boat will at least make folks think you know what you're doing!

A Word About Colors

Rockfish will hit just about anything if they are in the mood, however many times using a lure that's the right color makes all the difference. In order to understand the color issue, it's important to understand what happens to color at depth. The term "Selective Light Absorption" describes the fact that colors fade underwater. The first to go is red, which loses its intensity almost immediately underwater. By the time it reaches ten feet, it is no longer red and eventually fades to black at depth.  Orange and yellow are next, followed by other "cooler" colors, until, somewhere around 30 feet, everything fades to hues of green, blue, violet, gray and black. Even white takes on a grayish tint. Ultraviolet light, found after violet on the color spectrum, is invisible to human eyes, but apparently readily visible to fish. It appears that neon colors, when struck by invisible ultraviolet light, tend to "glow" or "fluoresce" at depth. Therefore a selection of neon colors should be considered for deepwater fishing. Since rubber "scampi" jigs are usually fished on or near the bottom, red or orange will accomplish little of benefit. Black is better but should be reserved for shallow water (30' or so), or for clear water or situations where fish are likely to silhouette your offering against light penetrating from the surface. Note that even in very clear water, there may be less than 1% of the available light at 300 feet than there is at the surface. Therefore a light-colored lure is likely to attract more attention than a darker one.

Orange and yellow are next, followed by other "cooler" colors, until, somewhere around 30 feet, everything fades to hues of green, blue, violet, gray and black. Even white takes on a grayish tint. Ultraviolet light, found after violet on the color spectrum, is invisible to human eyes, but apparently readily visible to fish. It appears that neon colors, when struck by invisible ultraviolet light, tend to "glow" or "fluoresce" at depth. Therefore a selection of neon colors should be considered for deepwater fishing. Since rubber "scampi" jigs are usually fished on or near the bottom, red or orange will accomplish little of benefit. Black is better but should be reserved for shallow water (30' or so), or for clear water or situations where fish are likely to silhouette your offering against light penetrating from the surface. Note that even in very clear water, there may be less than 1% of the available light at 300 feet than there is at the surface. Therefore a light-colored lure is likely to attract more attention than a darker one.

Regardless of the other colors in your tackle box, always include a selection of white scampi jigs. They are visible at just about any depth and is a natural color found on many baitfish. Most charterboats offer rods rigged with various colors. Go for the white jig, you can't go wrong.

Note that the use of artificial light is growing in popularity, and is proven to help you catch more fish. This is particularly true of ultraviolet lights. Lights come in various sizes and are secured to your line in the vicinity of your lure or bait. These lights are not only an attractant, they can restore natural colors to your offering.

Terminal Tacke for Halibut, Lingcod, and Rockfish

- Extra-large 10" scampi-type jig tails (2 white, 1 black)

- Medium 8" scampi-type jig tails (2 white, 1 black)

- Jig heads w/ hook (2 ea. 8oz.)

- Jig heads w/ hook (2 ea. 16 oz.)

- Kodiak Custom jigs (2 ea. 6oz., 10oz., 14oz., assorted colors)

- Swivels, large corkscrew-type, 12 ea.

- Circle hooks, size 8/0 - 16/0, 12 ea.

- J-hooks, size 8/0, 6 ea.

- Braided wire leaders, 18" heavy-duty w/Sampo ball-bearing swivels, 4 ea.

- Cannonball sinkers, 3 ea. 10oz., 16oz., 1.5lbs.

- "Hoochie" plastic squid lures, 8", 6ea. assorted colors

- "Crippled Herring" jig lures, 5oz., 2ea. in chrome, nickel/neon blue back, and pearl white.

- Sabiki Rigs for catching bait herring

- Hook file/stone

Rockfish Fishing Tips

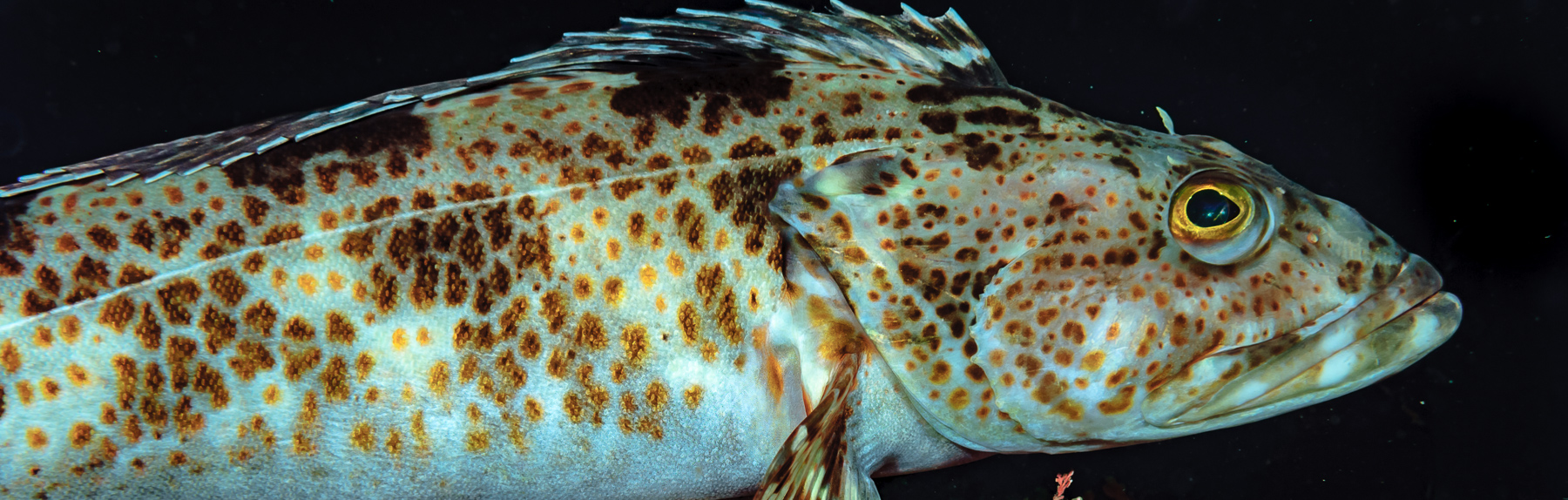

As was mentioned, Alaska has over 30 species of rockfish, offering tremendous variety to anglers. The most common rockfish in Alaska is the black rockfish, or sebastes melanops (sometimes mistakenly called a "black bass"). These fish can be found in schools numbering in the hundreds, or in small pods on rocky reef areas. Like all rockfishes, black rockfish are voracious feeders and strong fighters. They reach sizes up to 25 inches and weights over ten pounds. Though they are commonly found on or near the bottom, they also feed just about anywhere in the water column, and can sometimes be caught even on the surface.

One of the largest rockfishes (and one of the most highly prized fish) is the yelloweye. Sometimes mistakenly referred to as red snapper, the yelloweye is usually found at depths exceeding 250 feet, but they can be found shallower at times. They reach lengths in excess of 30 inches and are among the longest-lived rockfishes in Alaska, with some individuals over 120 years old. Their slow growth is one of the reasons that yelloweye receive more protection under the law than some other species.

Pelagic and Non-Pelagic Rockfishes

Rockfishes are generally divided into two categories: pelagic and non-pelagic. The term pelagic refers to the migratory nature of these fish, which becomes evident at different times of the year as they move in and out of different areas. Some common pelagic rockfish include:

Pelagics are frequently found together in mixed schools, however, the most predominant species is the black rockfish.

Non-pelagic rockfishes are not migratory and can therefore be found in the same areas year-round. For this reason, they can be quickly fished out once they are located, and care must be exercised to spread the fishing pressure around.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game restricts how many of each type of rockfish you may harvest. Pelagic rockfish are generally faster-growing than the non-pelagics, some of which may live as long as 120 years. A list of non-pelagic rockfish appears farther down on this page. If you reach your limit of non-pelagics and are fishing deep, it's best to either quit fishing or relocate. This is because bringing up fish from deep water can over-expand their swim bladder and damage or kill the fish.

Here is a list of the non-pelagics, which receive greater protection under the law:

- China Rockfish

- Copper Rockfish

- Quillback Rockfish

- Silvergray Rockfish

- Tiger Rockfish

- Yelloweye Rockfish

Rockfish are taken most frequently with bait (herring is a favorite), but they will also hit a variety of lures, including jigs, spoons, spinners, and flies. Fly-fishing for surface-feeding rockfish is exciting and fast-paced! The tactic is usually to scan for fish with a fish-finder, then lower your offering to the appropriate depth. They are sometimes taken by slow-trolling through prime habitat. Salmon anglers often encounter them this way.

Handling Rockfish

Care should be used in handling rockfish; most species have sharp dorsal and ventral spines, along with spines in the head and gill plates. Rockfish sometimes thrash around a bit while they are being unhooked, and it's easy to get a spine jammed under a fingernail or in the palm of your hand. Some species have venomous dorsal spines that, though not toxic, can create a painful wound that persists for days. Quillback rockfish are particularly known for this and should be handled with the greatest care.

Greenling

Greenling are related to lingcod, and are often found in the same habitat. There are two species of greenling in Alaska; the kelp greenling (hexagrammos decagrammus) and the rock greenling (hexagrammos lagocephalus). Both species are roughly the same size and are distinguished from each other mostly by color pattern. Rock greenling have large mottled color patterns ranging from olive to red, while kelp greenling show smaller spots and color blotches varying from electric blue to yellow and brown. There is significant color variation between male and female kelp greenling, with females showing brown and yellowish spots on a gray or brown background. Males are noticeably darker; grayish or olive-colored, with blue spots on the forward part of their bodies. They have no sharp spines and are commonly caught in the same habitat where rockfish are found. They can measure up to 24 inches in length, but the average is around 18 inches or so.

Greenling make excellent table fare; the meat has a fine texture similar to trout.

Releasing Rockfish

Catch-and-release fishing is commonplace in Alaska and is often done on saltwater charters when a non-target fish is taken, or when an angler catches a legal fish but wants to release it in order to keep fishing. Naturally, you should not gaff a fish that is intended to be released. Penetrating the fish with a gaff hook damages internal organs and creates a wound channel that can become infected and kill the fish. Also, avoid hauling fish over the rail and letting them flop around on the deck. A fish can bang its head on hard objects and it could receive serious injuries in the process. One of the best ways to release a fish is to net it with a rubber knotless net. These nets are very gentle on the fish, and greatly reduce damage to protective slime and scales. If possible, let the fish remain in the net during resuscitation, so it does not escape before it is fully revived.

Releasing a fish is usually a straightforward process, however, there are situations that require additional consideration or the fish could die.

Deep Water Release

For larger fish such as lingcod or halibut, it is best to take some time to resuscitate the fish before releasing it, especially if the fish fought long and hard and is fatigued. Grasp the fish firmly just in front of the tail, and use a gentle push-pull action to pump water over the fish's gills. If the fish rolls over on its side it is not strong enough to be released. Ideally, you should revive the fish until it swims off on its own.

In some cases, a fish is caught that has experienced barotrauma, a condition that occurs when a fish is hooked in deep water and quickly brought to the surface. Indications of barotrauma are protruding eyes and an inverted stomach that protrudes out of the fish's mouth. If a fish is directly released in this condition, it will float away and die on the surface. Read our special section on Deep Water Release for detailed instructions on how to properly release barotraumatized fish.

Terminal Tackle for Halibut, Lingcod, and Rockfish

Gear commonly used to catch halibut and cod works very well for rockfish as well. There is no need for special rigging.

- Extra-large 10" scampi-type jig tails (2 white, 1 black)

- Medium 8" scampi-type jig tails (2 white, 1 black)

- Jig heads w/ hook (2 ea. 8oz.)

- Jig heads w/ hook (2 ea. 16 oz.)

- Kodiak Custom jigs (2 ea. 6oz., 10oz., 14oz., assorted colors)

- Swivels, large corkscrew-type, 12 ea.

- Circle hooks, size 8/0 - 16/0, 12 ea.

- J-hooks, size 8/0, 6 ea.

- Braided wire leaders, 18" heavy-duty w/Sampo ball-bearing swivels, 4 ea.

- Cannonball sinkers, 3 ea. 10oz., 16oz., 1.5lbs.

- "Hoochie" plastic squid lures, 8", 6ea. assorted colors

- "Crippled Herring" jig lures, 5oz., 2ea. in chrome, nickel/neon blue back, and pearl white.

- Sabiki Rigs for catching bait herring

- Hook file/stone