Making the Shot on Alaska Big Game

Take a walk outside on a clear, moonless night and look at the stars above. Contemplate the fact that, for at least as far as you can see, to the most distant pinpricks of light in the blackness of space, our planet is the only place where life has been verified to exist. So regardless of whether or not we discover life elsewhere at some time in the future, we can at least agree that life in the universe is a precious commodity. And taking the life of a creature is a really big deal. As a hunter, it is your responsibility to make quick, clean kills every time. That means that in most cases, you must have firm control over all possible aspects of making the shot.

Caliber versus Shot Placement

Ask any group of hunters what the most important aspect is of shooting Alaska big game and you'll have a split over caliber versus shot placement, with both sides making convincing arguments to support thier perspective. Truth is, both are right, and hunters should consider both aspects to become a skilled shooter of Alaska game.

Caliber

The late Robert Ruark, in choosing the title for his book, "Use Enough Gun" simultaneously coined a phrase that has become the mantra of the big-bore club. And he was right; using a caliber that's adequate for the species being hunted is of paramount importance. Hunters must understand that "ultra-light" is for fishing, not big-game shooting. Choose a caliber that is adequate for killing the animal quickly and cleanly. But Alaska hunters must also remember that the entire state is also brown bear country. Though the possibility of a brown bear attack occurring is very remote, you must always be aware of the possibility and you should therefore choose a caliber that's not only adequate for the species being hunted, it must also be adequate for killing a brown bear quickly and at short range. In most cases this means that you must shoot a minimum of .30 caliber. If you want to know what really works, look to the Alaska big-game guiding community, where the following calibers are the most commonly carried in the field:

- 30.06

- .338

- .300 WSM

- .300 Weatherby

- .300 Win. Mag.

- .375 H&H

A projectile with enough mass to ensure good penetration, yet configured for expansion, will create hydrostatic shock and open a large wound channel, with cumulative fatal results. If you're shooting the 30.06, go with heavier bullets in the 200 grain range. The .375 calls for something in the 300 grain size class to do its job well.

Shot Placement

The ultimate big-game rifle and cartridge configuration does nothing for you if you can't shoot it well. Recoil-induced flinch is a common cause of misplaced shots in field conditions, so it's imperative that you choose a rifle from the list that you can consistently shoot well without worrying about felt recoil. It's also important that you become intimately familiar with the rifle and it's operation before taking it afield.

Rifle Range Tips

Good shot placement starts with building good shooting habits. The best place to do that is at the rifle range. Here are some basics to keep in mind when you're sighting in and practicing at the range.

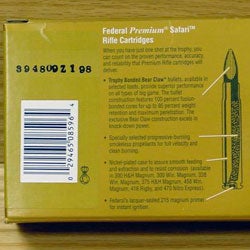

Use premium, consistent loads. Factory ammunition is loaded in batches, often called "lots", where many boxes are loaded at the same time. The lot number is stamped on each box before it is shipped. Choose premium ammunition of the same lot number for the most consistent results. Of course if you are reloading, sight in with the same hunting loads you will use in the field.

Use extra padding. Magnum calibers deliver magnum recoil. This is especially true at the bench, when you are leaning into the rifle a bit more than you would in the field. Insert some extra padding (a jacket, etc.) between the butt plate and your shoulder. The goal is to adjust the accuracy of the rifle, not see how much punishment you can take.

Shoot from a fouled bore. Keeping your rifle clean is very important, however a shot fired from a freshly-cleaned, oiled bore will often have a different point of impact than one fired from a fouled bore. You might as well fire the first shot into the backstop. After firing the last shot before you leave for the field, do not clean the bore.

Shoot from a Cold Bore. Wait ten minutes between shots. Your first shot taken at game in the field will be out of a cold bore. The hot loads typically fired from magnum rifles will heat up your barrel and influence the flight of your bullet. Allow the bore to cool between shots by opening the breech after firing and waiting ten minutes between shots.

Touch nothing forward of the receiver. The barrel has to whip when you fire. If you influence it by holding down on the fore-end, pulling down on the sling swivel or (worse yet) touching the barrel forward of the receiver, you'll change your point of impact. Cup the butt of the rifle with one hand and use the other to operate the safety and trigger.

Squeeze. Consciously discipline yourself to squeeze the trigger. Anticipating the recoil can cause you to flinch, pulling your shot. It should almost be a surprise when the rifle fires.

Try different shooting positions. Although most of your shots at game will be taken from a rest, you should practice shooting from various positions both from rests and offhand. Standing shots can be taken using a support pole for a rest, using shooting sticks or a spotting scope tripod, and offhand. Seated shots can be taken from the bench with a rest, and sitting on the ground, using your knees to anchor yourself. Finally, do a few prone shots. In the field, prone shooting opportunities are rare because of obstructing vegetation, but you should be comfortable with that position in case it presents itself in the field.

Use a spotting scope. The spotting scope saves you from walking downrange after your shots. Use the time instead to let the bore cool.

Use a scope and iron sights. It's possible that you could damage your scope in the field. If your rifle is equipped with iron sights, you can continue hunting. If not, you're hunt is over. Shoot with your scope and your iron sights so you are comfortable with both.

Shoot three-shot groups. Fire your shots in three-shot groupings before making adjustments to your sights or riflescope. Don't adjust the rifle after only one shot. Occasionally you'll get a round that is inconsistent (a "flyer"), and you don't want to base your adjustments on that round.

Use a spare target for scoring. Mark your shots on an extra target kept at the bench. This allows you to keep good track of your shots and adjustments.

Zero in at 200 yards. Though the distance you need to shoot depends on the location you're hunting, zeroing your rifle in at 200 yards presents the optimal adjustment for most Alaska hunting situations. Much of the country here is open and you should rarely take a shot beyond this distance. Though longer shots are often a point of pride for the shooter, extremely long shots increase your chances of wounding game. Shorter shots are more humane and respectful of your quarry.

Try different distances. If you're doing your job correctly, most of your shots will be taken at around 100 yards. But in cases where you've wounded an animal and it is escaping, you have an obligation to dispatch it quickly. Practice your offhand and rest shooting at various yardages and note the results in terms of bullet drop. Practice a lot so you know what you can do at various differences.

Learn to estimate range. The advent of modern rangefinders has eroded some hunter's ability to accurately estimate yardage. Use a rangefinder to check your estimates until your proficiency increases. Accurate yardage estimations are critical to taking game cleanly.

In the Field

Making a shot in the field is much easier if you're familar with your rifle and know what it will do at various yardages. Assuming you have invested the time in learning the rifle, together with it's limitations and yours, the following tips will help you take game with little suffering to the animal.

Get Close

Stalking to within a hundred yards or less is the single best thing you can do to take game humanely. Learn to read the wind, manage your scent, manage your movement, and make quiet stalks. Use the terrain features to mask your scent and movements, and to funnel the animal's movements to pre-selected ambush points.

Scent Management

Scent management is a skill best acquired with years of field experience. The movement of air currents over the land is perhaps the single greatest betrayer of your presence, so learn to read the wind and learn to understand how it plays across the landscape. Air flows in a manner similar to water flowing in a river. There are back-eddies, flow reversals (vertical and horizontal), and inversions in addition to areas of consistent flow. All of these things are influenced by obstructions the wind encounters as it flows through. It's important to understand this in order to make undetected stalks on game. Identifying air movements before your stalk begins is critical to planning your stalk, and can save you many wasted steps. Watch the movement of the grass, leaves, and the angle of falling rain or snow to determine where the likely traps are, and avoid them.

Camouflage scents and attractor scents are not commonly used in Alaska. It's best to learn to use the wind to screen your approach. That said, a low level of cover scent can be accomplished by sitting around the campfire and letting the woodsmoke penetrate your clothing. Avoid scented soaps for your body and even scented laundry detergents for your clothing.

Read the Land

Before you begin your stalk, scout the terrain with your binocular to locate unforeseen ravines and other obstacles that could waylay your plan. If possible, choose a shooting location before you begin your stalk, and map out pathways around or through brush. Realize that the terrain will look completely different as you get on it, and choose landmarks along the way to help you stay on track. Remember that the longer the stalk, the greater the chances that the animal will have moved while you were approaching it. Anticipate where the animal is likely to go as it moves.

Keep it Quiet

Most hunters know to avoid making noise during a close stalk. Pay special attention to squeaky pack frame pins (tape them in place with electrical tape), noisy clothing that makes a racket in the brush and avoid talking. At the same time when hunting moose, realize that they are somewhat more tolerant to noise than other deer species, especially during rut. Often they will come in to investigate the sound of a stick breaking while you walk. It's different with bears. With them, you've got to go with total stealth.

The Final Approach

In most cases a close approach to the animal is the best way to ensure a clean kill. This usually means getting to no more than 100 yards from the animal. Take your time and ensure that the animal does not know you are there. Choose a solid rest, chamber a round and ensure that there are no obstacles (leaves, blades of grass, twigs and such) between your rifle's muzzle and the animal. Make sure you have good visibility of the kill zone and that the animal is not moving. Then take your time to ensure a good shot.

Big-Game Targets and Shot Placement Guides

One of the best ways to learn shot placement on big game animals is through game targets and shooting guidebooks. Check out these resources from the Alaska Outdoors Supersite Store (click the title to order):

- Perfect Shot North American Edition, by Craig Boddington

- Perfect Shot mini edition north America pocket guide Part 1, by Craig Boddington

- Perfect Shot mini edition north America pocket guide Part 2, by Craig Boddington

- Black Bear target

- Dura Mesh archery black bear target

- Dura Mesh Moose target