Alaska Moose Hunting

Moose are the quintessential big-game animal of Alaska. Commonplace in the most urbanized areas of the state, they are accessible, relatively easy to hunt, and unique. To the trophy hunter, moose antlers are an imposing memento of a hunt, and the meat hunter will harvest enough meat from this animal to last a year or more.

Biology

There are four subspecies of moose inhabit North America:

- Eastern Moose (alces alces americana): The moose of the northeastern United States and eastern Canada.

- Western Moose (alces alces andersoni): Found in all Canadian provinces except Newfoundland and Labrador. Some are found in GMU 1 in the Alaska Panhandle region.

- Shiras Moose (alces alces shirasi): Scattered populations in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Washington, Wyoming and parts of Canada.

- Alaska-Yukon Moose (alces alces gigas). This is the moose of Alaska and parts of Canada's Yuon Territory.

Three other species of moose are recognized; the Eurasian Elk (alces alces) of Estonia, Finland, Norway, Sweden and parts of Russia, the Siberian Moose (alces alces bedfordiae) of Siberia, Mongolia and Manchuria, and the Caucasian Moose (alces alces caucasicus) of Eastern Europe’s Caucasus Mountains; thought to be extinct. Stories and photos of Siberian moose taken by hunters make it appear that the Siberian moose is at least equal in size to the Alaska-Yukon moose, however data is inconclusive on that point.

Moose calves are usually born in May, and predation on moose calves is common, with predators taking between 50% and even 100% of calves some years, depending on the location. Common predators of moose calves in Alaska are black bears, brown / grizzly bears, wolves and coyotes. Within two weeks of its birth, a moose calf is usually strong enough and nimble enough to escape most predators. Cows typically keep calves nearby for the first two years of life, after which calves wander off on their own.

Moose are primarily browsers, dining on leafy vegetation in the spring, summer and fall months. They transition over to twigs and will also strip bark from trees during winter. They will on occasion eat spruce, a tree passed up by most other browsers. During the summer and fall, they prefer willow if they can get it, and for this reason, savvy hunters concentrate their efforts on large willow patches.

Winter droppings are easily distinguished from summer droppings. During winter moose are eating woody browse  (twigs and bark), and they don’t get as much water because everything is frozen. During this time their droppings are oval, about a half-inch long, and are distinct from each other. The composition of the scat appears almost like rough sawdust. Summer and fall droppings are more cohesive, and can even resemble bear scat or cow patties. When you’re scouting moose country, look for summer and fall droppings to confirm moose will be in the area during hunting season. If all you see are “moose nuggets” and closely-browsed brush, you may be in a wintering area that will be mostly devoid of moose during the fall hunting season.

(twigs and bark), and they don’t get as much water because everything is frozen. During this time their droppings are oval, about a half-inch long, and are distinct from each other. The composition of the scat appears almost like rough sawdust. Summer and fall droppings are more cohesive, and can even resemble bear scat or cow patties. When you’re scouting moose country, look for summer and fall droppings to confirm moose will be in the area during hunting season. If all you see are “moose nuggets” and closely-browsed brush, you may be in a wintering area that will be mostly devoid of moose during the fall hunting season.

Bulls remain solitary for most of the spring and summer, while antlers are developing. By late August to early September the velvet starts to dry and is stripped off when a bull thrashes brush with his antlers, or rubs them against trees and other vegetation.

Generally speaking, the pre-rut period begins as antler velvet begins to dry and antler thrashing commences, and continues until the tenth of September. During this period bulls may remain in bachelor groups, and will vocalize to an extent. After September tenth, bulls become much more vocal and antler thrashing turns to fighting with other bulls. Fighting can become severe at times, breaking antler tines and causing injury to one or both bulls involved. In some cases, entire antlers have been snapped off close to the pedicle (base). Pre-rut bulls also dig rut pits with their front hooves, urinating on the ground and stamping with their hooves to create an aromatic mud that often coats the lower legs and belly area in the process. They don’t usually wallow as do elk, consequently rut pits are usually much smaller than an elk wallow. Cows have been observed wallowing in rut pits, however. As the season progresses, bulls may develop harems of cows, with typical harems consisting of anywhere from one to four or five cows. Larger harems occur, but are less common in areas with a healthy population of bulls. Breeding takes place in late September through October.

Seasons

The general moose hunting season in Alaska begins between the first and the tenth of September, and lasts until the last week in September. Check the hunting regulations, as areas open and close at different times. Moose are often hunted in conjunction with other species such as caribou, black bear or brown / grizzly bear. However, though caribou and moose may inhabit the same general areas, caribou are mostly creatures of the open, treeless tundra, while moose are found in river bottom areas or other places with plenty of sheltering vegetation.

In some parts of Alaska winter hunts may be conducted. Tags for these hunts are typically available by drawing permit.

Hunting Tactics

Hunting tactics remain similar from one part of Alaska to another, but may vary with the timing of the hunt. The two primary methods used are glassing and calling. Let’s look at each method in more detail.

Glassing for Moose

Glassing is more commonly referred to as “spot and stalk” hunting. Hunters seek a vantage point that affords a view of the area, and once a legal bull is spotted, a plan is made to approach it on foot undetected. Most inexperienced Alaska moose hunters are very surprised at the amount of time required for glassing. It’s not uncommon to remain at a spotting location for many hours, returning to the same location for several days. The primary drivers for this have to do with low bull density and scent management. In the former case, hunters must understand that though Alaska has the largest variety of game animals of any state in the country, the density per square mile is among the lowest. In layman’s terms, there’s a lot of terrain out there that doesn’t have a big game animal on it for most of the year, if at all. That means you need to remain on-station for many hours, in most cases.

The second issue, scent management, is important because moose have an uncanny sense of smell. Though they can accommodate themselves to the presence of humans fairly easily, they may avoid humans in places where they do not expect to encounter them. Generally speaking, moose will gradually filter out of an area with human scent. On some hunts, it’s not uncommon to see several moose early in the hunt, but fewer and fewer as you approach your second week in the field. Hunters who are accustomed to climbing every hill and descending every valley in search of game (Idaho elk hunters, for example), usually end up with little more than a good workout. On the other hand, the hunter who remains in a fixed glassing location stands a much better chance of taking a bull. That’s because the mobile hunter spreads his scent throughout the area, whereas the scent of the stationary hunter pools in one area or plumes downwind. The other factor is that the stationary hunter is more likely to spot movement of game at a distance, because he is motionless. For the hiking hunter, everything is in motion and animal movements at a distance are difficult or impossible to detect. In short, sit still and you’ll see more moose.

The second issue, scent management, is important because moose have an uncanny sense of smell. Though they can accommodate themselves to the presence of humans fairly easily, they may avoid humans in places where they do not expect to encounter them. Generally speaking, moose will gradually filter out of an area with human scent. On some hunts, it’s not uncommon to see several moose early in the hunt, but fewer and fewer as you approach your second week in the field. Hunters who are accustomed to climbing every hill and descending every valley in search of game (Idaho elk hunters, for example), usually end up with little more than a good workout. On the other hand, the hunter who remains in a fixed glassing location stands a much better chance of taking a bull. That’s because the mobile hunter spreads his scent throughout the area, whereas the scent of the stationary hunter pools in one area or plumes downwind. The other factor is that the stationary hunter is more likely to spot movement of game at a distance, because he is motionless. For the hiking hunter, everything is in motion and animal movements at a distance are difficult or impossible to detect. In short, sit still and you’ll see more moose.

Comfort is the key to good glassing efforts. Bring a folding chair, or find a comfortable place to sit. Bring along a chunk of a closed-cell foam pad to sit on; it provides padding and insulates you from the cold, hard ground. Here’s a short list of items you should have with you on the spotting hill, in addition to your regular hunting gear:

- Comfortable seat (foam pad, chair)

- Raingear

- Insulating layers of clothing (including hat and gloves)

- Mosquito headnet

- Spotting scope, tripod

- Binocular

- Backpack stove, cookpot

- Hot drink mixes, dried soup packets, freeze-dried meal

- Snack items

- Water bottle (full) and water filter

Glassing Locations

Choosing the best location from which to glass is a critical decision on your hunt. The most obvious locations are areas of high ground adjacent to good habitat. An elevated perch allows you to see down into the willows instead of trying to look through them at the same level. This makes it easy to spot openings where animals can be more easily seen at a distance. Tree stands are a good choice in areas of relatively flat terrain, for the same reasons. If you’re hunting relatively flat areas, don’t overlook glassing opportunities across ponds, openings and gravel bars. If you’re hunting a river where the primary habitat is in the riparian zone (the river bottomland), your best glassing opportunities might be to hike through the riparian zone out onto the tundra. Find a comfortable spot and glass back toward the edges where moose are more visible as they come out to feed.

Glassing Techniques

Use a strategy when you’re glassing, or you could overlook important details. Look the area over with your naked eye first. This is the best way to spot movement from a distance. From a distance a moose standing broadside often looks like a black rectangle (bears are more rounded in appearance). Generally moose will appear darker in bright lighting, and may blend in more in the flat light you get on an overcast day. Once you’ve given the area a good once-over with your eyes, get the binocular out and focus on areas of habitat that could hold moose. Some talk about using a grid method to take the area apart for glassing purposes, but it’s more effective to first focus on patches of willow that are likely to hold moose. Finally, don’t expect to see an entire moose standing broadside. Most often you will see parts of a bull, obscured by vegetation or terrain. If a bull is bedded, you may see only the tops of his antlers. Antler color is another consideration. Early in the season, as soon as the velvet comes off, antlers may show a reddish appearance. But with the velvet removed, they take on a bone-white appearance which is easily visible from a distance. Later in the season after the bull has had the opportunity to rub his antlers on brush and tree limbs, the antlers take on a brownish hue from the tannins in the vegetation.

Calling

As was mentioned earlier, calling is a primary tactic for hunting Alaska’s moose. Bulls make a number of sounds in the early part of the season (before September 10th), and become noisier as the season progresses. Good callers capitalize on this tendency and have a greater chance of success. Bulls and cows make different sounds, but both calls can be used to attract bulls. The bull call is often a short and guttural, “errough”! Sometimes they call as they are walking, grunting with each step. You can imitate that behavior by making five or six short grunts in succession, with a couple of seconds between each call.

Bulls also call by thrashing their antlers against a tree or the surrounding brush, an unmistakable sound that can be heard sometimes at a distance of a mile. Because bulls will sometimes knock dead trees over in their fury, it’s almost impossible to overdo it when you’re thrashing the brush. The simplest form of thrashing is done with a large stick three or four inches in diameter. Rake the tree with it, breaking other dry limbs in the process. Break other dead branches from the tree, and rake them up and down the trunk. A dried moose scapula (shoulder blade) makes an excellent scraper, as it has a sound similar to the antler on a smaller bull. If you have a bull coming in and he hangs up in the brush, you can sometimes draw him out by holding the scapula over your head at a 45-degree angle, gently waving it back and forth to simulate a young bull posturing with his antlers.

Cow calls are longer and more drawn-out than bull calls, and can be heard at distances over three miles in the right circumstances. A cow call may continue for thirty seconds or more, quavering and finally tapering off at the end.

A megaphone is often used to project cow or bull calls over long distances, and you should have one in your gear. The traditional moose megaphone is made of birch bark, and you can make it yourself in the field. Be careful to strip off only the top layer of birch bark though, or you will kill the tree. A commercially-produced fiberglass megaphone is also available, and has been used with great success in Alaska.

Regions / Places to Hunt Moose in Alaska

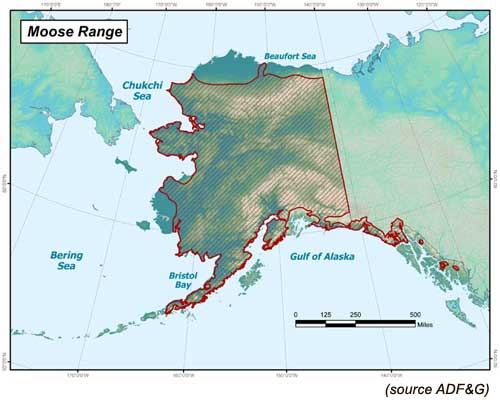

Moose can be found in much of Alaska, though populations in some areas is thin. Here's an overview of moose distribution across the state.

Region 1 (Southeast Panhandle)

Game Management Units: GMU 1, 2, 3, 4 & 5

Region 1 South: Southeast Panhandle | Region 1 North: Yakutat / Cordova Area

Available species:

Black Bear | Brown / Grizzly Bear | Deer | Elk | Goat | Moose | Wolf

Southeast Alaska is not generally recognized as a moose hunting mecca, due to poor habitat quality and subsequent low densities. GMU 1 has some moose hunting by drawing permit, but the Yakutat / Cordova area is a much better prospect, with better habitat and larger numbers of moose. Yakutat moose hunting is by drawing permit, but Cordova has a general harvest season in addition to some drawing hunts. There are no moose on Prince of Wales or Admiralty, Baranof or Chicagof (the ABC Islands). The species available in GMU 1 are thought to be alces alces andersoni (Western Moose), commonly found in Canada.

Region 2 (North Gulf Coast, Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak / Afognak Archipelago

Game Management Units: GMU 6, 7, 8, 14C, 15

Region 2 East: North Gulf Coast / Kenai Peninsula | Region 2 West: Kodiak / Afognak Archipelago

Available species:

Bison | Black Bear | Brown / Grizzly Bear | Caribou | Dall Sheep | Deer | Elk | Goat | Moose | Wolf

Historically, the Kenai Peninsula has offered some of the best moose hunting in Alaska. But that was around the early 1900’s following some major fires that resulted in excellent moose browse for many years. More recently, most of the Kenai Peninsula is covered in mature spruce forests, which has crowded out much of the willow. This has resulted in reduced moose numbers in many areas of the Kenai. Moose hunting here is managed by general season tags, and by drawing permits. Numbers have fluctuated on the Kenai Peninsula over the years, and recent wildfires will result in habitat / browse improvements which should contribute to better moose production. There are no moose in the Kodiak / Afognak island group.

Region 3 (Interior, central & eastern Brooks Range)

Game Management Units: GMU 12, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26B, 26C

Region 3 East: Eastern Arctic / Eastern Interior | Region 3 West: Central Interior

Available species:

Bison | Black Bear | Brown / Grizzly Bear | Caribou | Dall Sheep | Moose | Wolf

Moose numbers are very low north of the Brooks Range, however huntable numbers are found farther south of the Continental Divide. The area bordering the Yukon River is covered in black spruce forests that extend for miles. Moose live in these areas, but density is low. Farther south into the Interior moose habitat improves dramatically. Hunting throughout the region is managed mostly on a general season basis, however there is no nonresident moose season north of the summit of the Brooks Range (GMU 26).

Region 4 (Southcentral, Alaska Peninsula, Aleutians)

Game Management Units: GMU 9, 10, 11, 13, 14A, 14B, 16, 17

Region 4 East: Southern Interior, Anchorage, Susitna Valley | Region 4 West: Bristol Bay and the Alaska Peninsula

Available species:

Bison | Black Bear | Brown / Grizzly Bear | Caribou | Dall Sheep | Goat | Moose | Wolf

The eastern Interior offers good moose opportunities, however access is limited. Hunting conditions improve substantially north of Anchorage and out into the Susitna Valley and over the Alaska Range to the west into GMUs 19, 17 and 21. Currently the area is recovering from a significant predator issue. Wolves and bears had increased to the point that moose seasons had to be closed for a while, or severely limited. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game intervened with several predator control measures that have apparently given moose a break and numbers are on the rise. Moose numbers on the Alaska Peninsula are relatively low, and managed on a drawing permit basis. Best chances are in the Iliamna / Lake Clark area, but habitat quality falls off as you move west along the Peninsula.

Region 5 (Western Brooks Range, west coast to Bristol Bay)

Game Management Units: GMU 18, 22, 23, 26A

Region 5 North: Western Arctic | Region 5 South: Yukon / Kuskokwim Delta

Available species:

Black Bear | Brown / Grizzly Bear | Caribou | Dall Sheep | Moose | Muskox | Wolf

The Western Arctic has huntable populations of moose, however it has gone to drawing permit for nonresidents. Farther south in GMU 18, habitat quality is good and moose are found in huntable numbers.

Additional Resources

"Is This Moose Legal? " A DVD by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. This DVD is designed to educate hunters on how to judge moose antler spread, brow tine count and other indicators used to determine the legality of a particular bull moose. Hunters unfamiliar with judging legal moose are encouraged to watch this DVD. The video also includes an excellent second feature titled, "Field Care of Big Game"; an excellent instructional video on how to field dress and pack a moose.

"Love, Thunder & Bull ", and "Love, Thunder and Bull 2 ". These two DVDs, by Wayne Kubat of Alaska's Remote Guide Service, are the single best resource available to hunters who want to learn how to call moose. With lessons on bull calls, cow calls, and other methods for attracting moose, these DVDs are an excellent addition to a moose hunter's library.

"The Bull Magnet ". This is the megaphone you need to call moose from long distances. Featured in Wayne Kubat's moose calling DVDs, it's a "must have" for hunters planning on hunting the pre-rut and rut periods.

"Hunt Alaska Now", by Dennis Confer; an excellent book that contains lots of how-to instruction on hunting Moose in Alaska, in the context of self-guided hunts.